When I was preparing to write this article, I did a quick google search to check whether "boobie shells" were a thing. The results were populated entirely by sites selling silicone ‘shells’ for collecting breast milk. After perusing the products, I narrowed down the search by adding a single word. Only then did I come across a single reference to boobie-shaped coral on Reddit. So, it turns out boobie shells are something that exist in my mind alone. Until now, people!

That single word I added to the search was "urchin". Because boobie shells are not shells at all. Well, at least not ones that contain a mollusc. Instead, they are part of an exoskeleton from a dead sea urchin.

Sea urchins are what is known as echinoderms, a group that also includes starfish and sea cucumbers. Being a taxonomist, I love a good Greek root… *cough*, you know, linguistically.

Anyway, echinos is the Greek root word meaning spiny and derma means skin. Spiny skin, so original.

Echinoderms, including sea urchins, are recognisable by their five-point radial symmetry. If you don’t believe me, go count the arms on a starfish. They also have a water vascular system that they use to move around the seafloor. This involves filling and emptying tiny tubes ending in suction pads for grip with water like a hydraulic conveyor belt under the body of the echinoderm. When filled, the tubes push the creature along then empty again in what looks like a line of inflatable tube men doing the Mexican wave.

In the Illawarra, the most common sea urchin washed up on the shore is the purple sea urchin Heliocidaris erythrogramma, which actually comes in an array of colours from deep purple to pink to green. This fact once convinced scientists that the different colours corresponded to three different species, not merely colour variations of the same species as is known now.

You might have spotted the remnants of this sea urchin species or another washed up on the shore. Depending on how long the animal has been dead, there might be spines attached or you might be left with the hard exoskeleton that protects the soft internal body of the urchin, called the "test". Sea urchin tests can be extremely beautiful and are one of my most coveted ocean treasures, made more precious by their fragility.

Once the animal dies, the connective tissues that hold the spines to the test break down and the spines fall away. The place where each spine joins the test is marked by a small raised bump that looks for all the world like a tiny marine nipple.

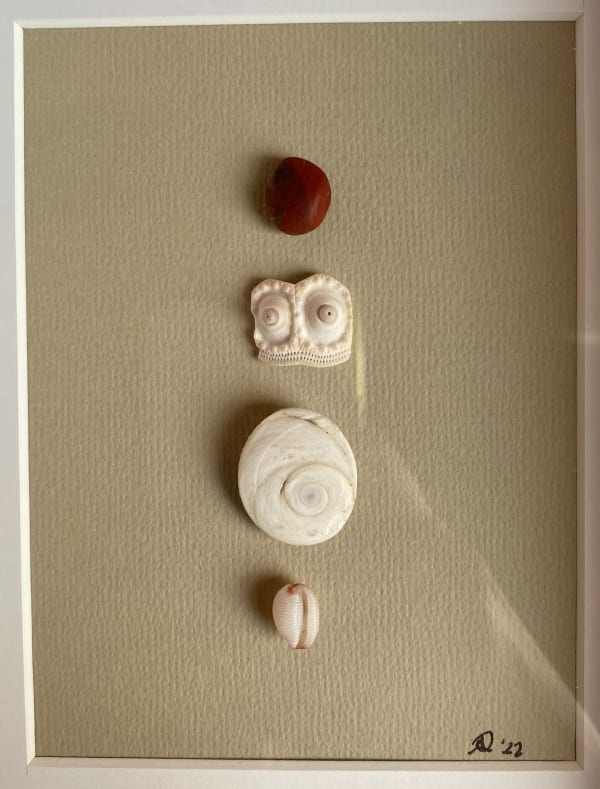

The best find is the rarest of all: an urchin test that has been broken up and now consists solely of two little nipple plates side by side to create a pair of boobs.

I’m a breastfeeding mum and I also have an affinity for finding patterns. Patterns in nature, in concepts, in behaviour. And there is something oddly satisfying to me about the convergence of evolution that facilitated the development of nipple-like organs in two very different creatures for two very different purposes. I think it’s beautiful. So much so that I sometimes create art with these shells, borne of a desire to pay tribute to the beauty, strength and consonance of the female form. The form is enduring and beautiful in every facet and purpose, something you might only look to the ocean to realise.

So, here’s to hoping I’ve started a thing. Or at least I hope to create one more search result for people to discover if they happen to find a pair of boobies staring up at them from the sand and are curious enough to want to know what created such a joyous piece of art.