By Mariani, University of Nottingham; Anna Florin, Australian National University; Haidee Cadd, University of Wollongong; Matthew Adeleye, University of Cambridge, and Simon Connor, Australian National University

Increased land management by Aboriginal people in southeastern Australia around 6,000 years ago cut forest shrub cover in half, according to our new study of fossil pollen trapped in ancient mud.

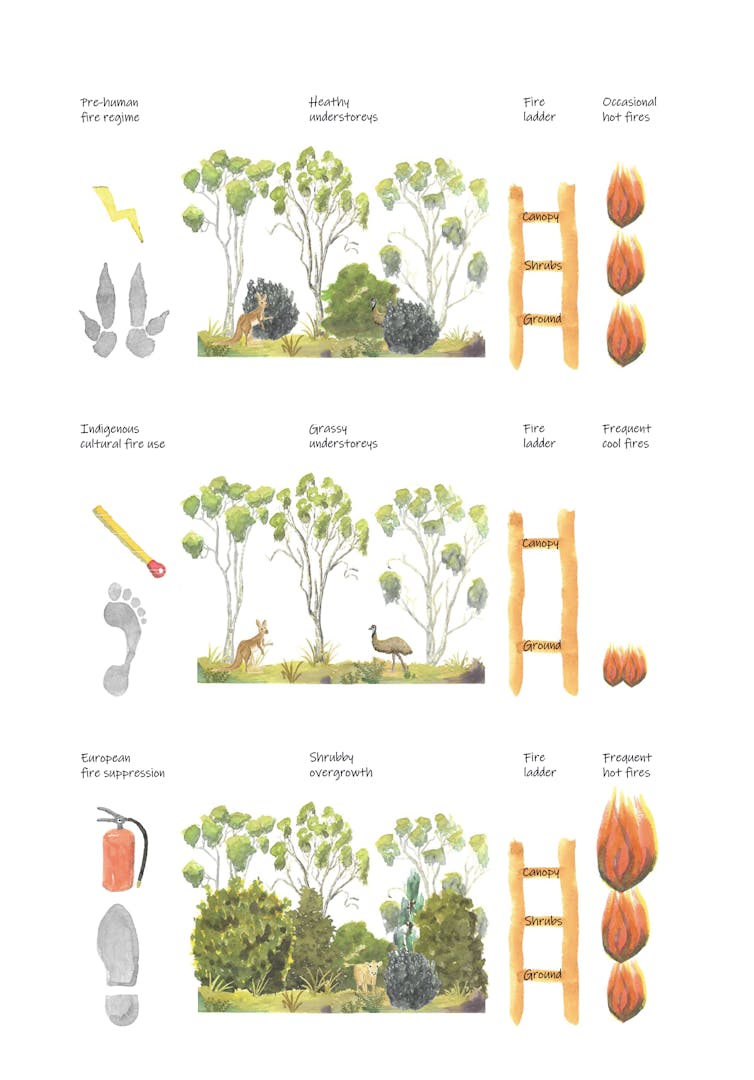

Shrubs connect fires from ground cover to the forest canopy, allowing fires to spread and intensify quickly. The reduction in shrub cover, linked to evidence for increasing population size and more widespread landscape use by Aboriginal people, would have dramatically decreased the potential for high-intensity bushfires.

We also found the shrub layer in modern forests is even greater than it was 130,000–115,000 years ago, when the climate was similar to today’s but there were no people around.

Our deep-time research shows how important Indigenous cultural practices were for reducing dangerous high-intensity fires. It also suggests a way forward in Autralia’s current fire crisis, which climate change is making worse.

The trouble with shrubs

For decades, Australia has tried to manage fires by suppressing them. This strategy may be effective in the short term, but it has led to dire consequences in the long term.

Over the past 20 years, the forests and woodlands of southeastern Australia have become hotspots for major fires.

Fire suppression has allowed vegetation, particularly in the shrub layer, to grow without constraint. Shrubby, mid-height vegetation acts as a ladder, enabling fires to spread up from the ground to the forest canopy. This results in more intense and uncontrollable fires.

Evidence for denser vegetation comes from tiny, fossilised grains of pollen that are laid down in layers of ancient sediment in wetlands and lake beds. By extracting fossil pollen from mud, scientists can develop a picture of vegetation in the past.

Our new study used archaeological data and information preserved in ancient mud. We looked at how the vegetation of southeastern Australia changed in response to climate and human management over the past 130,000 years.

We wanted to see how things changed in key periods: before human arrival in Australia, through periods of Indigenous occupation, and following British colonisation.

We used sophisticated models to estimate vegetation cover and how it related to human land use at different times.

Caring for Country

Indigenous Australians have been the custodians of this continent for millennia. Their journey in Australia started at least 65,000 years ago.

Direct evidence of cultural burning traces back at least 11,000 years in the Top End, although it may have begun much earlier.

Indigenous Australian cultural burning practices are complex and varied. However, in many parts of the continent they included regular, controlled burns. These helped to manage vegetation growth and reduce the risk of high-intensity fires.

Since British colonisation, the landscape of Australia has undergone significant changes, with both more open pastures and more densely vegetated forests. The introduction of European land management practices, including fire suppression, disrupted the fire regimes Indigenous Australians had maintained for thousands of years.

This suppression-focused approach has led to an accumulation of plant matter, creating a tinderbox ready to ignite.

A call for change: integrating Indigenous Knowledge

To address this crisis, a shift in fire management strategies is essential. One promising approach is to integrate Indigenous fire management practices into contemporary fire management plans, working with Traditional Owners to best care for Country.

This must be done in a way that supports Indigenous livelihoods and fosters connection to Country, not by management agencies simply appropriating Indigenous know-how.

Indigenous Australians possess hundreds of generations’ worth of experience in managing the country’s fire-prone landscapes. Indigenous-led fire management is already being reinvigorated in northern Australia.

Our research demonstrates that southeastern forests and woodlands were effectively managed in the past and would also benefit from Indigenous caring-for-Country practices today.

Reducing dangerous fuels in the shrub layer means less high-intensity fires threatening the bush–urban interface, such as the 2019–20 Black Summer fires.

Higher temperatures and prolonged droughts have created ideal conditions for bushfires to spread. Colonisation has compounded the problems arising from human-driven climate change.

But there is no fire without fuel. It is the combination of increased biomass and a warming climate that now fuels fires of unprecedented scale and intensity, posing a significant threat to lives, property and ecosystems.

Australia’s fire crisis is a complex issue that requires a multifaceted solution. By learning from and working with Indigenous practitioners, Australia can develop more effective and sustainable fire management strategies. This collaborative approach offers a path forward to tame the flames and protect the nation’s unique and diverse landscapes.![]()

Michela Mariani, Associate Professor in Physical Geography, University of Nottingham; Anna Florin, Lecturer in Archaeological Science, Australian National University; Haidee Cadd, Research associate, University of Wollongong; Matthew Adeleye, Assistant Professor of Physical Geography, University of Cambridge, and Simon Connor, Fellow in Natural History, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.